The sparse vectors created with this package will act as a drop-in replacement for dense vectors in any workflow. You will not see a memory penalty for doing this. This is happening because non-compatible operations will simply materialize the full vector and it would behave as if you didn’t create it sparse to begin with.

This is generally the truth, but there are some cases where it isn’t. This article will lay out when and how you can use sparse vectors for the best performance possible.

To aid users in determining whether the code is not dropping the

sparsity, the option sparsevctrs.verbose_materialize can be

set to alert the user that a sparse vector was forced to

materialize.

options("sparsevctrs.verbose_materialize" = TRUE)Base size of objects

One of the differences between sparse and dense vectors is how much memory they take up. This value is computed as an offset plus a linear effect based on the number of values.

An integer vector of length 0 takes up 48 B to exist.

Each additional value adds another 4 B on average. This

effect is linear, so an integer vector with 1000 elements takes up

48 B + 1000 * 4 B = 4048 B, an integer vector with 2000

elements takes up 48 B + 2000 * 4 B = 8048 B and so on.

obj_size(integer(0))

#> 48 B

obj_size(integer(1000))

#> 4.05 kB

obj_size(integer(2000))

#> 8.05 kB

obj_size(integer(3000))

#> 12.05 kBThe vectors above only contained the value 0. We can

replicate that sparsely with

sparse_integer(integer(), integer(), length = 0). We see

that the size of a 0-length sparse integer vector has a size of

888 B.

obj_size(sparse_integer(integer(), integer(), length = 0))

#> 888 BThis value is the same for any size of sparse vector, regardless of how long it is. This is happening because the sparse vectors only keep track of the non-default values.

obj_size(sparse_integer(integer(), integer(), length = 0))

#> 888 B

obj_size(sparse_integer(integer(), integer(), length = 1000))

#> 888 B

obj_size(sparse_integer(integer(), integer(), length = 2000))

#> 888 B

obj_size(sparse_integer(integer(), integer(), length = 3000))

#> 888 BKeeping dense data in a sparse format

A dense integer vector will have the same size, regardless of what values it takes

dense_x <- integer(1000)

obj_size(dense_x)

#> 4.05 kB

dense_x[1:100] <- 1:100

obj_size(dense_x)

#> 4.05 kBThe sparse integer counterpart on the other hand will increase for each non-default we need to store.

sparse_x <- sparse_integer(integer(), integer(), 1000)

obj_size(sparse_x)

#> 888 B

sparse_x <- sparse_integer(1:100, 1:100, 1000)

obj_size(sparse_x)

#> 2.07 kB

sparse_x <- sparse_integer(1:200, 1:200, 1000)

obj_size(sparse_x)

#> 2.47 kBSo it all comes down to a trade-off. Dense integer vectors with a size of 210 or less will be smaller than their sparse counterparts no matter what. Dense integer vector vectors with 211 elements will take up the same amount of memory as their sparse counterpart with no values.

From these values we can calculate memory equivalent vectors to

determine which would be more efficient, noting that sparse vectors

increase in size by twice for each non-default value that their dense

counterpart. For a vector of length 1000, the sparse vector will be

equivalent in size if it has 210 non-default values. And

these values continue to go up.

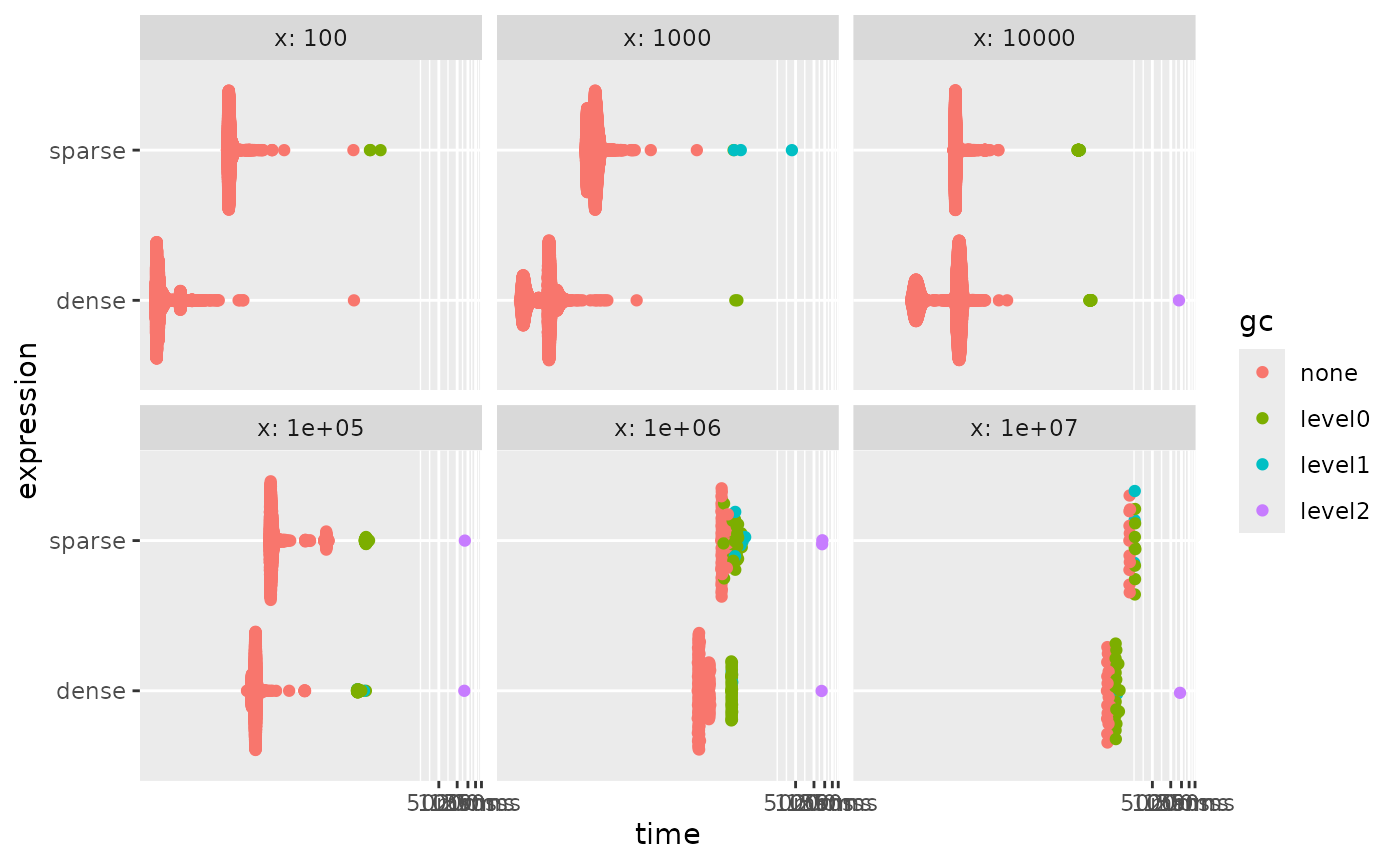

Conversion speed

As with everything in life, we have to deal with tradeoffs. The main tradeoff you will see in using this package is that memory allocation is minimized to allow for workflows not otherwise possible. With that in mind, there will be times when using these sparse vectors is not ideal. The main one is that converting back and forth between dense and sparse vectors takes a non-zero amount of time. Generally, you won’t see any benefit if you are forced to materialize a sparse vector.

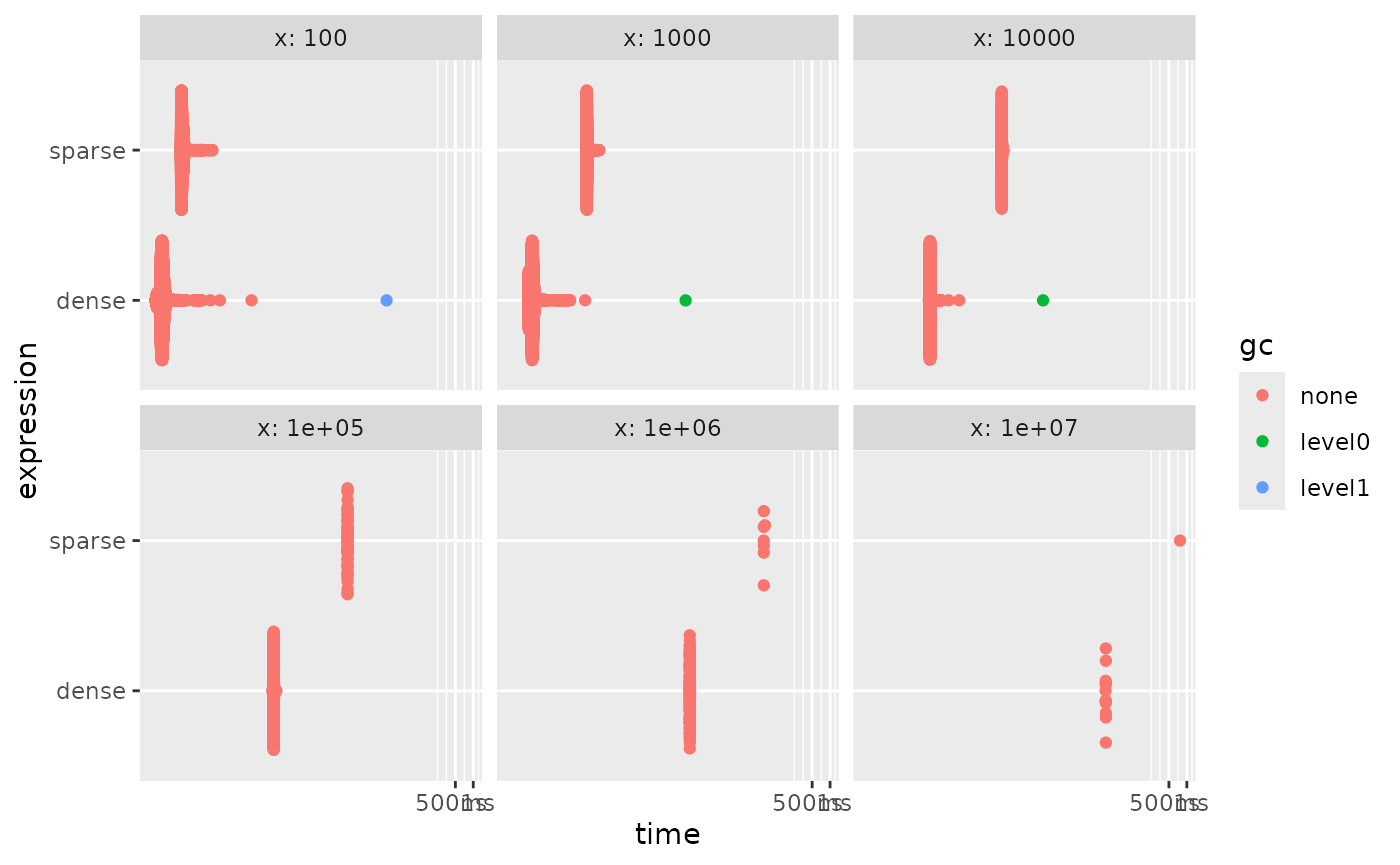

Below is one such example. both dense_fun() and

sparse_fun() creates a numeric vector, with length

x, with the value of x in the last element.

Calling [] on an ALTREP vector forces it to materialize, so

we now can look at how much slower it is to create the sparse vector and

go back.

dense_fun <- function(x) {

res <- numeric(x)

res[x] <- x

res

}

sparse_fun <- function(x) {

res <- sparse_double(x, x, x)

res[]

}

bench::press(

x = c(10, 100, 1000, 10000, 100000, 1000000),

{

bench::mark(

dense = dense_fun(x),

sparse = sparse_fun(x)

)

}

) |>

autoplot()

staying dense the whole time is faster no matter the speed.

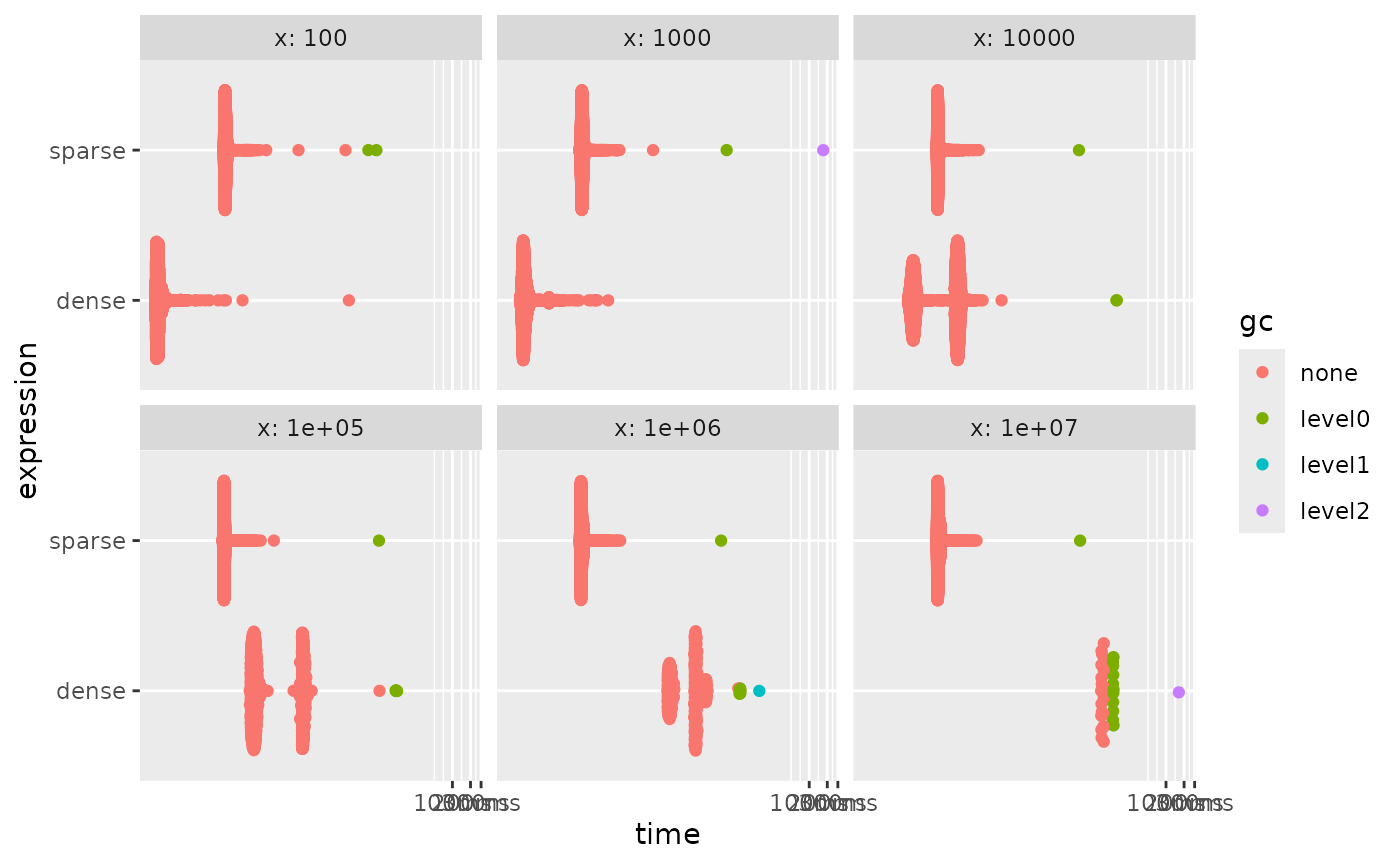

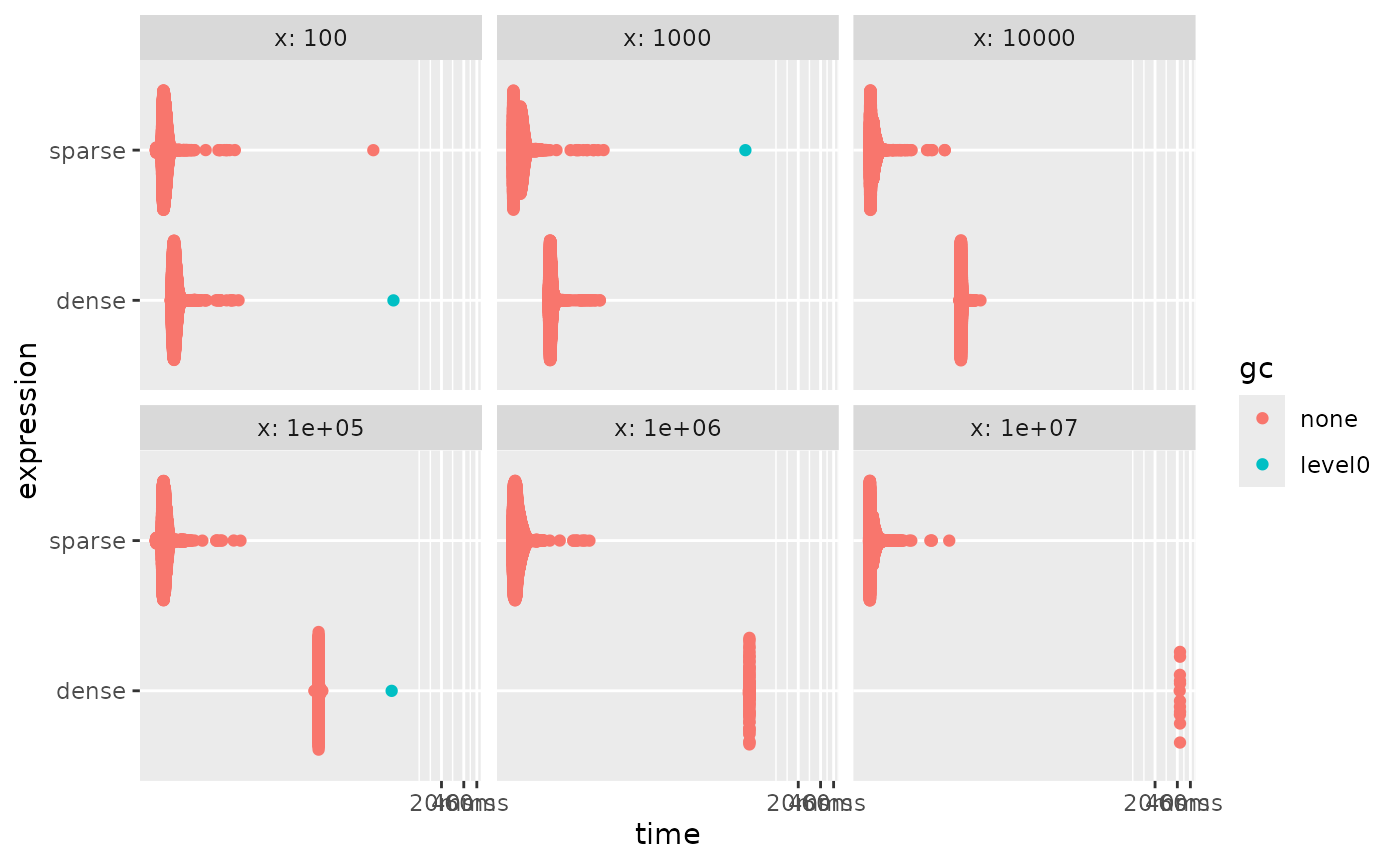

As a comparison, we can look at how much time it takes if we don’t force materialization.

dense_fun <- function(x) {

res <- numeric(x)

res[x] <- x

res

}

sparse_fun <- function(x) {

res <- sparse_double(x, x, x)

res

}

bench::press(

x = c(10, 100, 1000, 10000, 100000, 1000000),

{

bench::mark(

dense = dense_fun(x),

sparse = sparse_fun(x)

)

}

) |>

autoplot()

What we are really seeing here is that creating a sparse vector takes

a near-constant amount of time. So once the length is high enough it

wins. But this by itself isn’t a good comparison because these vectors

are useless unless we do something with them. Where sparse vectors shine

is when we can use sparse-aware methods. One such example are

min(), max() and sum() for

numeric ALTREP vectors. These functions have special hooks to trigger

implementations that don’t require materialization. They will thus do

quite well.

dense_fun <- function(x) {

res <- numeric(x)

res[x] <- x

res

}

sparse_fun <- function(x) {

res <- sparse_double(x, x, x)

res

}

bench::press(

x = c(10, 100, 1000, 10000, 100000, 1000000),

{

dense_x <- dense_fun(x)

sparse_x <- sparse_fun(x)

bench::mark(

dense = sum(dense_x),

sparse = sum(sparse_x)

)

}

) |>

autoplot()

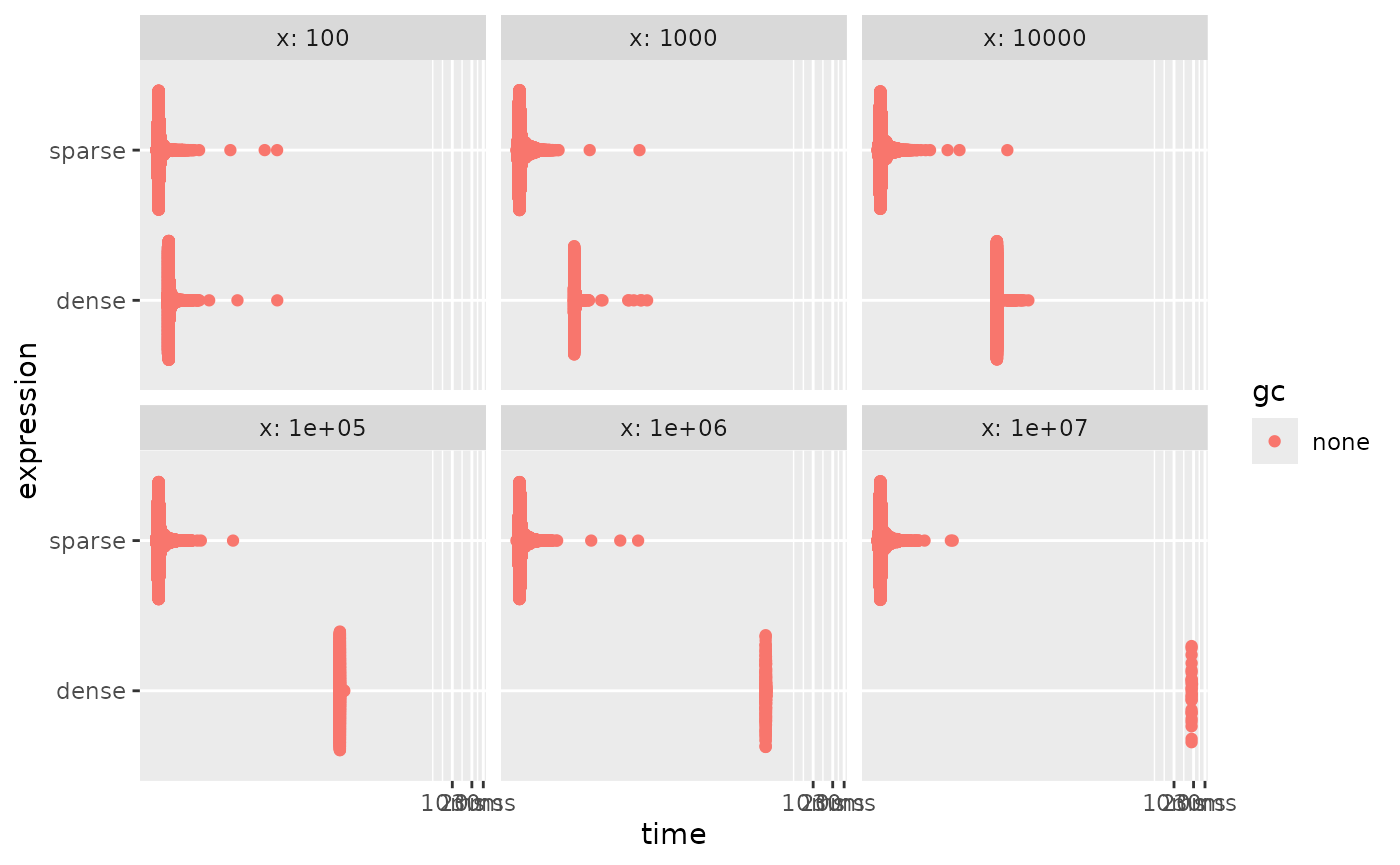

These functions do well because they calculate the sum over the

non-default values instead of all values. For truly sparse vectors this

will be fast. On the other hand, some methods don’t have ALTREP support.

Trying to use them triggers materialization to allow the calculations to

progress. Once such unsupported method is mean().

dense_fun <- function(x) {

res <- numeric(x)

res[x] <- x

res

}

sparse_fun <- function(x) {

res <- sparse_double(x, x, x)

res

}

bench::press(

x = c(10, 100, 1000, 10000, 100000, 1000000),

{

dense_x <- dense_fun(x)

sparse_x <- sparse_fun(x)

bench::mark(

dense = mean(dense_x),

sparse = mean(sparse_x)

)

}

) |>

autoplot()

And we see that the sparse is always slower. But this can be handled

by doing sparse-aware calculations. The helper functions

sparse_positions() and sparse_values() can be

used in combination with other functions to work with sparse vectors

without having to materialize them. Under the assumption that

default = 0, we can write a mean method for sparse vectors

as sum(sparse_values(x)) / length(x). Using this

formulation allows us to work fast again by avoiding

materialization.

dense_fun <- function(x) {

res <- numeric(x)

res[x] <- x

res

}

sparse_fun <- function(x) {

res <- sparse_double(x, x, x)

res

}

sparse_mean <- function(x) {

sum(sparse_values(x)) / length(x)

}

bench::press(

x = c(10, 100, 1000, 10000, 100000, 1000000),

{

dense_x <- dense_fun(x)

sparse_x <- sparse_fun(x)

bench::mark(

dense = mean(dense_x),

sparse = sparse_mean(sparse_x)

)

}

) |>

autoplot()

The ideal usage of sparse vectors is to keep them in a data.frame or

tibble, and use coerce_to_sparse_matrix() at the end to

create a sparse matrix that is understood by downstream functions.